Non-Motherhood Is Complicated

Image via @porchlightbooks

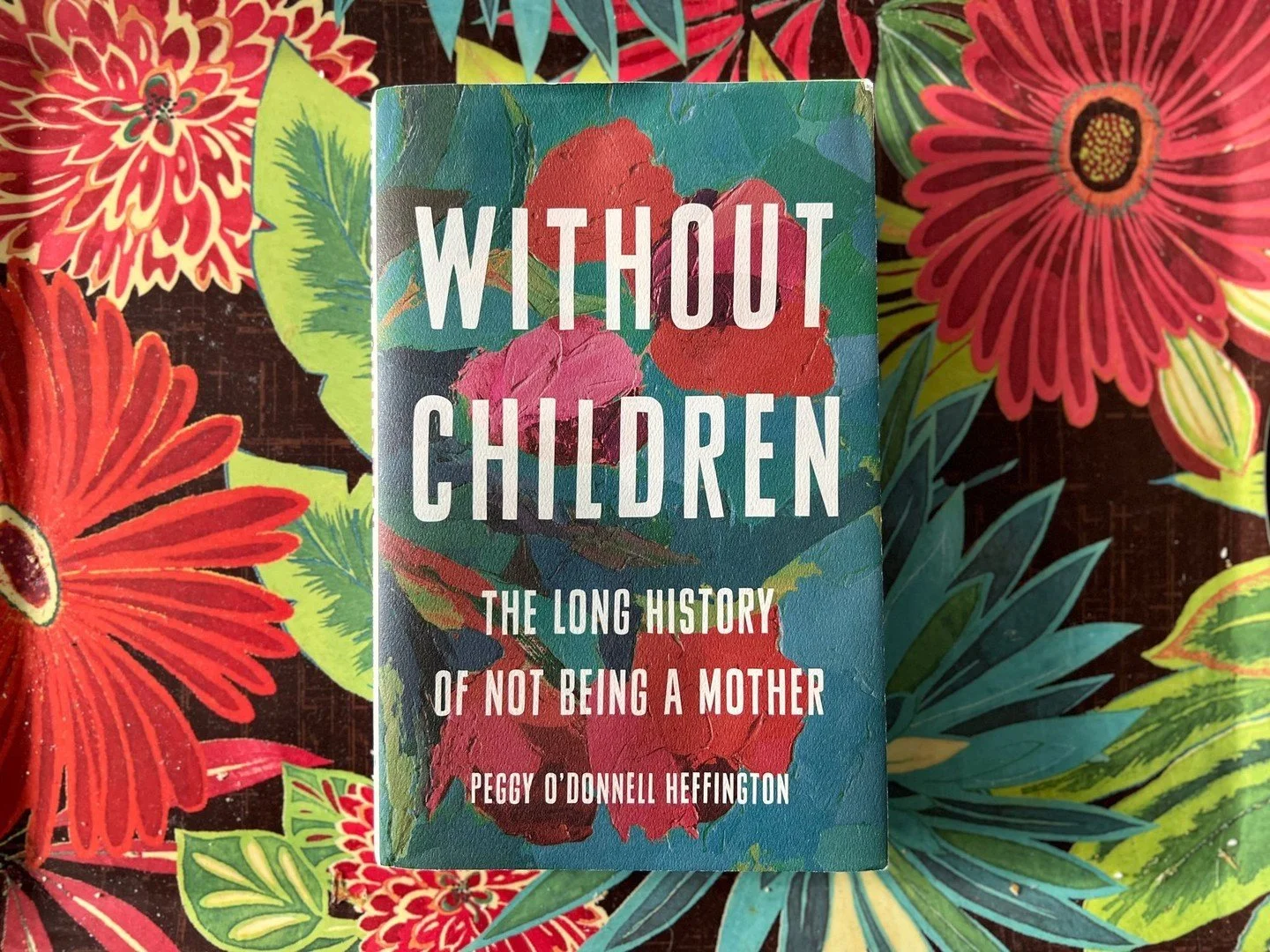

Excerpted from “Without Children: The Long History of Not Being a Mother”, by Peggy O’Donnell Heffington. Copyright © 2023. Available from Seal Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Over the past four decades, studies from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have consistently found that very few women are willing to label themselves “voluntarily childless”: 6 percent in 2017, up just slightly from 4.9 percent in 1982. Another researcher found that 5 percent or so identify as “involuntarily childless,” usually meaning that they wanted children but infertility intervened.

For the rest of us, the majority without kids, our non-motherhood was arrived at slowly, indirectly, through a series of decisions that sometimes had nothing, and yet everything, to do with reproduction: to go back to school to get a graduate degree and change careers, to leave a loveless marriage at thirty-five, to take a job far from family networks that could have provided support, to hold out for a partner who makes you happier than you can make yourself, to look hard at the fires and floods and storms that augur climate catastrophe within the next generation’s lifetime.

In some cases, the choice was made for us, by jobs without paid parental leave or the dizzying cost of day care or our staggering student loan payments or the careful math it takes in twenty-first-century America to own a home or ever hope to retire.

Some of us tried fertility drugs or IUI or IVF, decided to stop when it got too expensive or physically grueling, and exist in a gray zone between choosing not to have children and not being able to. We are what one scholar calls “perpetual postponers,” women who might have been mothers had our lives broken another way or the society we live in been different — whose biological clocks struck midnight, or taste for sleepless nights ran out, or aging parents began needing care before having a baby made even the least bit of sense.

The explanations for individual and collective childlessness are complicated. It’s not just our finances, or the joy of living a selfish and hedonic existence, or the grief of infertility. For some of us, it’s all of these, and more: the lack of support in our current society that makes parenting a profoundly individual, isolated project; the financial pressures that make us prioritize careers and income over almost anything else; the fear of raising children on a planet already groaning under the weight of a mass of humanity doing its best to destroy it; the fear of creating another human to aid in that destruction. Some of us want to live lives that don’t allow space for children, lives that demand we spend our reserves of time, energy, and love in other ways.

None of these reasons are new. History is full of women who may have wanted kids badly, or been ambivalent about them, or been freed by not having them, but who in any case never did have them. They were not having children long before the highly effective forms of birth control we have today existed, and long before feminist theory began to tease out the space between motherhood and womanhood. In our struggle to build our lives and to figure out whether those lives allow for children, we are products of our historical moment, of the tiny gift of time we have been given on this planet. But history also tells us we are not alone.